Celiac disease: An autoimmune response

Celiac Symptoms — classic and non

The classic and most immediately noticeable symptoms of celiac disease are, not surprisingly, gastrointestinal: bloating, flatulence, and diarrhea, sometimes with smelly stools. People who can’t digest gluten or grain sugars may have similar symptoms.

Celiac disease can severely impair the absorption of nutrients. In children, this may lead to stunted growth; in adults, the consequences include anemia (because iron isn’t being absorbed) and weaker bones (because calcium and vitamin D aren’t getting into the body). Anemia causes fatigue and malaise, but some people with celiac disease feel that way without anemia.

Doctors sometimes miss the celiac disease diagnosis because they’re looking for the classic gastrointestinal symptoms, not the vaguer ones that stem for the most part from malabsorption of nutrients.

One major difference between celiac disease and grain-related digestion problems is that when it’s just a digestion problem it typically doesn’t lead to malabsorption and nutritional deficiencies.

Women with untreated celiac disease have higher-than-normal rates of menstrual abnormalities and infertility. A large study published in 2007 found an increased risk of pancreatitis in people with celiac disease. It’s not clear whether a cause-and-effect relationship can be inferred from these associations or if celiac disease and these conditions happen to be consequences of a shared, common cause.

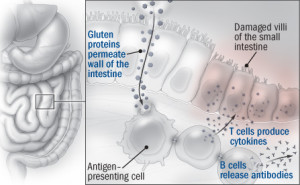

According to some research, several of the nongastrointestinal conditions associated with celiac disease might be caused by an overabundance of antibodies that the immune system churns out, especially those it produces in response to an enzyme in the small intestine called tissue transglutaminase. The antibodies travel to other parts of the body through the bloodstream. Perhaps the clearest example of one of these antibody-related symptoms is a skin condition, dermatitis herpetiformis, which causes itchy red bumps. Less certain is whether the anti–tissue transglutaminase antibodies might get into the brain and cause neurological problems, such as loss of muscle control (ataxia).

A blood test and a biopsy

Compared with other autoimmune disorders (such as Crohn’s disease and rheumatoid arthritis), the diagnosis of celiac disease is pretty straightforward. In the United States, the issue has been getting doctors to consider the celiac diagnosis as a possibility. That’s changing. For example, the guidelines for irritable bowel syndrome were revised to include testing for celiac disease.

The diagnosis begins with a blood test for the antibodies generated by the immune response that gluten provokes. Tests exist for several different types of antibodies, but the one for the antibodies against the tissue transglutaminase enzyme is the most reliable and accurate. If the blood test is positive, the next step is biopsy of tissue from the small intestine to see if the villi have been damaged. Collecting the biopsy involves snaking an endoscope — a flexible tube with a tiny camera on the tip — down the throat and through the digestive tract and snipping out small pieces of tissue that can be examined under a microscope.

Dr. Daniel Leffler, a celiac disease expert at Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, says the biopsies show, on average, that over 90% of people with positive antibody tests and celiac symptoms have intestinal damage, and the presumption is that they have celiac disease. But if the biopsy shows a lack of intestinal damage, that usually rules out celiac disease as a diagnosis.

In people with symptoms, judging whether there’s a favorable response to a gluten-free diet isn’t difficult: the turnaround from illness to health can be quite dramatic. But Dr. Leffler notes that many — indeed, perhaps most — people with a positive antibody test and intestinal damage do not have symptoms or have atypical ones that are subtle and vague. These patients raise some important questions. Is this a case of test results in need of a disease, rather than the other way around? And from the patient’s perspective, why bother with a diet that’s inconvenient — despite the growing number of choices — and expensive if you don’t have symptoms?